ECONOMY MONITOR

The Italian economic reminds us of the ugly duckling: at times it seems like a fairy tale, but in fact it is solid, driven by investments, exports and employment

by Fabrizio Galimberti and Luca Paolazzi

The Italian economy is growing more – or slowing down less – than the Eurozone: What are the factors that explain this performance? And what other stumbling blocks lie in wait for the global economy? Why has the Chinese rebound not lived up to its promises? Inflation is falling: but perhaps not enough? The trend in benchmark rates: which ones are continuing, which are slowing and which are stopping? Where is the USD going? Are stock prices overvalued?

REAL INDICATORS

“Once upon a time there was an ugly duckling…” Everyone knows the happy ending of Hans Christian Andersen's fairy tale, capable of tormenting its characters, the children reading who identify with it, with stories bordering on cruelty, before letting them breathe a sigh of relief at the end.

The amazing recovery of the Italian economy post-pandemic has some fairy tale elements, but nothing miraculous, as it is the child of difficult transformations and voluntary corrections in European macroeconomic policies. We will tell you the story and frame it within the current global context.

The background, or the period of ugliness. From the beginning of the new millennium to the last year pre-COVID, the growth of Italy's economy was completely unsatisfactory. Along the way, we lost more than one percentage point of GDP growth per year compared with the other major countries in the single currency.

Cumulatively, this comes to over 20%: for a household, it would be like not earning or spending anything after mid-October, then starting again in January, compared with a German or French household. An extreme case of belt tightening! And to think that the Germans whine that Italians are like cicadas, handing out generous pensions to one and all (which is another piece of false news if you consider the average pension actually received).

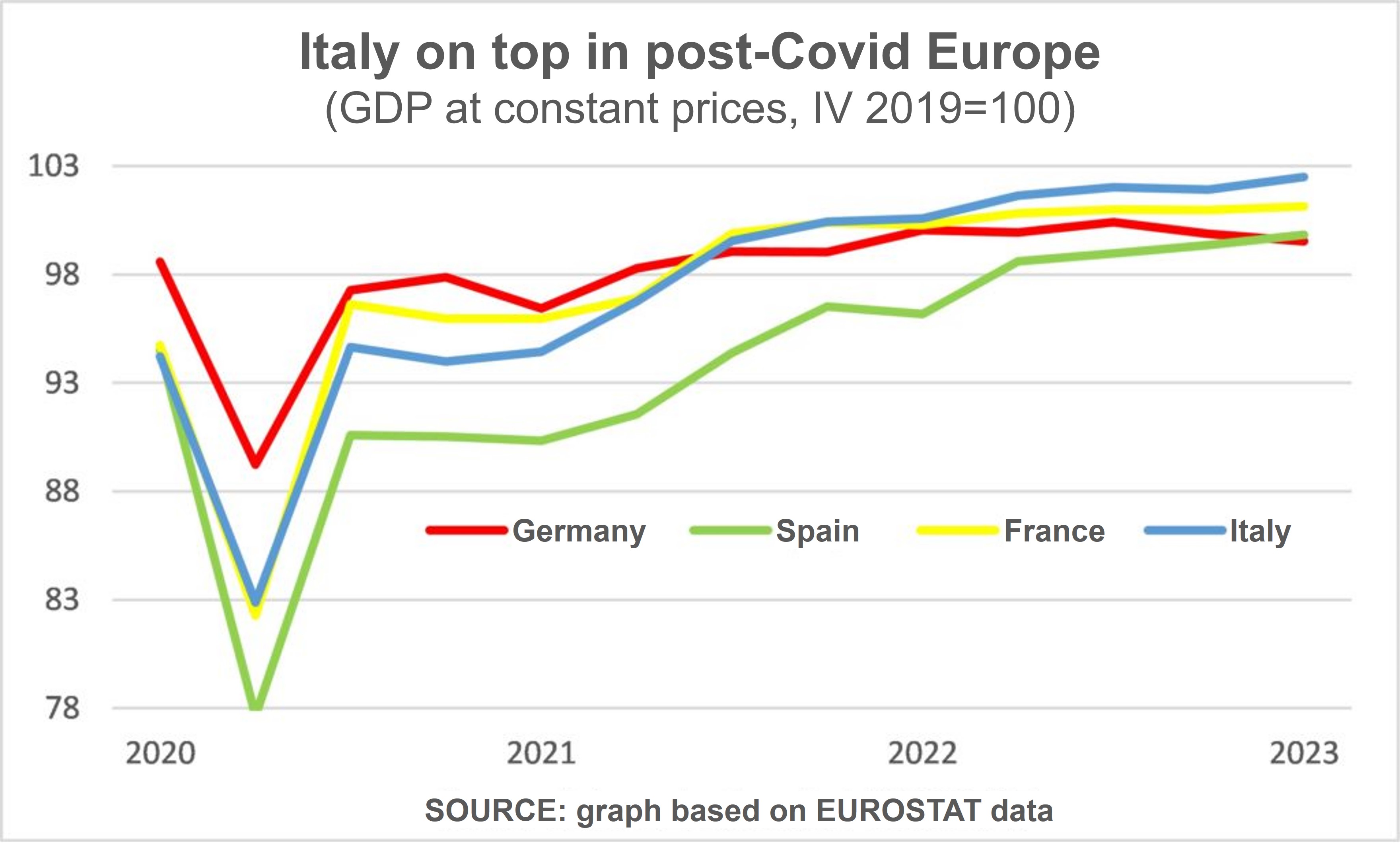

Then, since the start of the recovery from the COVID crisis, the pace of the Italian economy has speeded up faster than the others: in the first quarter of 2023 the increase in GDP was significantly higher than that of Germany, France or Spain.

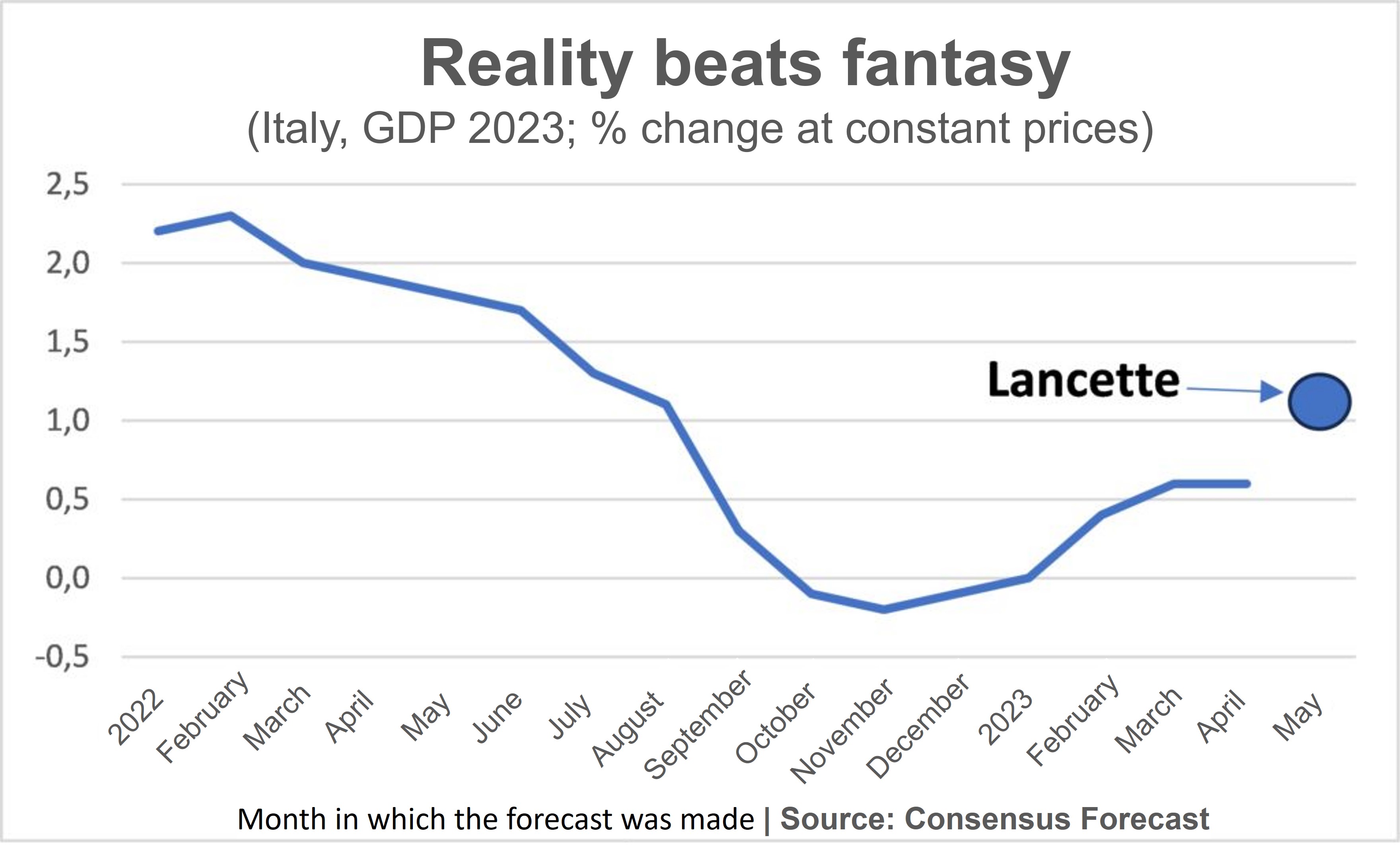

The difference between the growth forecasts for 2023 made in 2022 and the results actually achieved has also been surprising: at a certain point last year, the initial forecasts indicated a real reduction for this year, albeit a small one.

Now the actual result is 0.9% and it is highly probable that the final figures will be a few tenths of a percentage point higher than that. Of course, some were even more drastic: Cassandras who beat their breast, announcing that recession was just around the corner due to the war, the double whammy from energy and food, and the rapidly rising cost of money. But more than the tightened belt, albeit loosened slightly by government policies, other factors may have contributed to this situation. And the observation that reality has surpassed the forecasts makes it necessary to look for the reasons why and to understand if they are solid or short-lived.

If we use the scalpel of statistics to dissect the demand components which have gone from strength to strength, we can identify exports and capital investment. The former also includes tourism, and anyone who travels the length and breadth of Italy will see armies of visitors filling up trains, restaurants, streets and squares, as if it were their last chance to travel in life. But the former also comprises the competitive ability of the business system, aided by a trend in the cost of labour, which is much lower than that of our European competitors. Companies are riding the wave of innovations with their capital investments, the second component that is moving very fast. Helped by home renovations (thanks to the government's infamous building bonuses) and public works.

Unit cost competitiveness and new systems (even a café adding tables outside creates greater production capacity) have generated record employment, which gives some extra cash to households impoverished by price hikes. This allows them to increase their consumption, in a dance of supply and demand, which resembles that of the planets chasing the sun, moving around the centre of the Milky Way (at an unthinkable speed).

THE ITALIAN ECONOMY: WILL THIS GROWTH LAST?

Will this dance continue, or as in the game of musical chairs will we have to stop at some point with someone being eliminated? The experience of recent years has taught us the cardinal virtue of prudence, because ugly ducklings become swans, but if they are fundamentally tarnished, nothing is going to clean them. Let's take a look at what will remain and what will disappear, knowing that we can distinguish fairy tales from reality, above all thanks to our experience of reality. Certainly, the fact that we have conquered market shares in goods and tourism will continue to make us grow, providing customers' trust has been fulfilled and their general experience satisfactory, and we have no reason to doubt it. The same goes for the advantage that Italy has in its cost of labour. However, it may be worth reflecting on how attractive these wages are for young people, many of whom are leaving Italy.

On the other hand, with regard to the rise in capital investment in the building industry, it is legitimate to ask the following question: will the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP) and the other funds allocated by Draghi's government be used to keep actual growth high and therefore raise potential growth? This is a historical opportunity, one of those that comes along every couple of generations. The government that knows how to take advantage of it will be able to boast about it for years to come. The government that doesn't will see the beautiful swan turn back into an Ugly Duckling; or the carriage and the horses back into a pumpkin and mice, according to another fairy tale whose origins are less Nordic and therefore to be taken very seriously.

Markets as well: the spread between BTPs and Bunds – the litmus test of 'Italy risk' – remains calm, as does the other 'test': the spread between BTPs and Bonos. Especially since there is another structural reason for this: the improved health of the banking system (copyright Ignazio Visco). On the other hand, budget policy effectively supported households and businesses in the dark times of the pandemic, improving their finances and creating reserves ("private stashes") which allowed them to keep spending, both consumption and investments, as soon as COVID loosened its grip.

As for the rest, the international economic framework continues to be in favour of Italy. The figures for Italy's SMEs are still positive, albeit more for services than for manufacturing (as evidenced by the further decline in industrial output in April). But this is a gap that can be seen almost everywhere. We will take a look at the reasons for it next month.

We can now see that we have left behind the unending worry of the US public debt limit, but there are "new sufferings, new sufferers, surrounding me on every side" – as Dante wrote – and we could write too, given that other threats, both economic and political, are waiting at the horizon. On the one hand, there are growing tensions over Ukraine, where, amid drone attacks on Moscow, more incursions into the Russian city of Belgorod (with a number of people killed), dams blown up and massive flooding, the war is getting nastier. The high tension between the US and China is continuing, accompanied by signs of a slowdown in the European economy (with the Eurozone – but not Italy – in a 'technical recession'), but not the Chinese one.

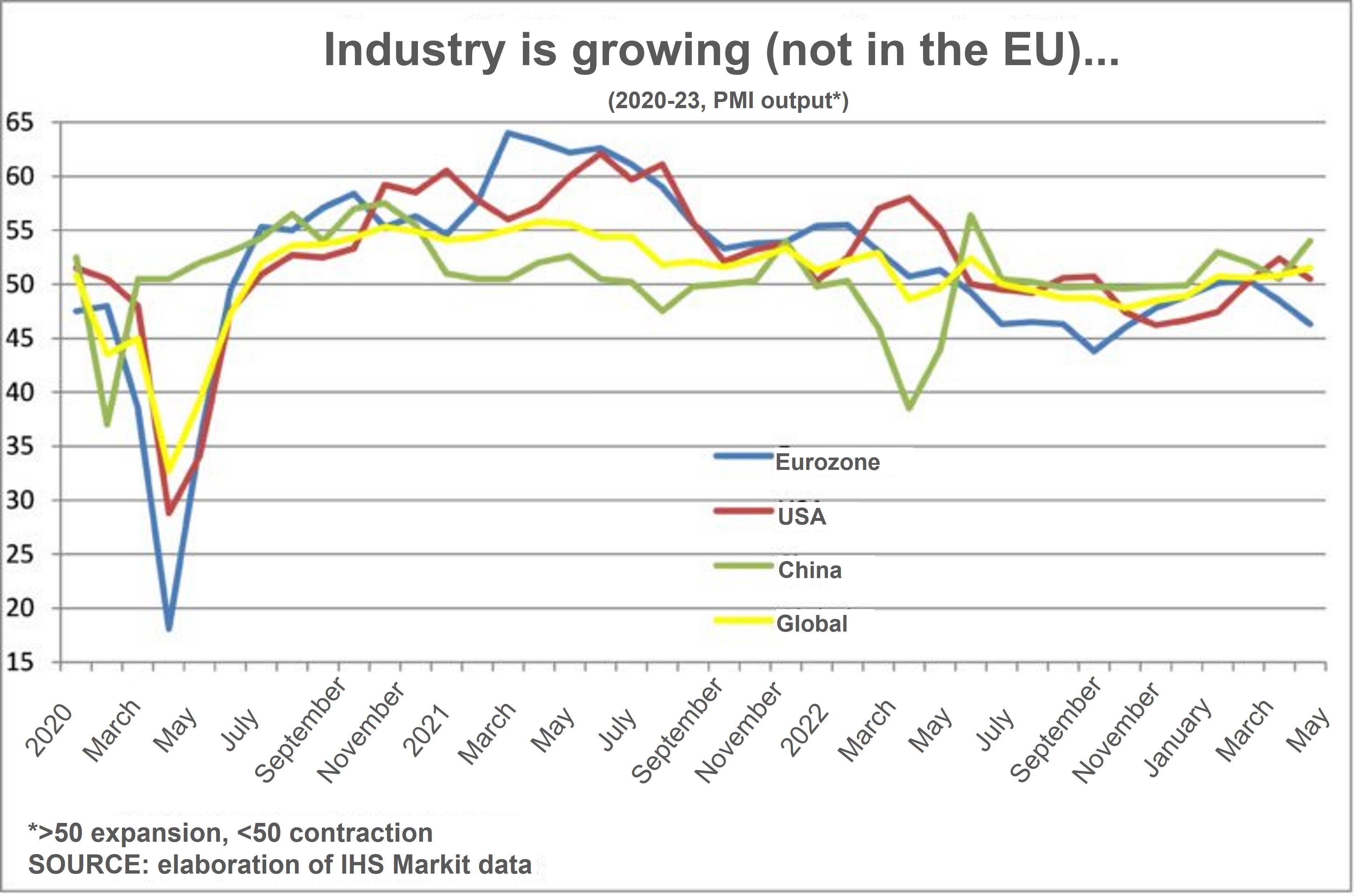

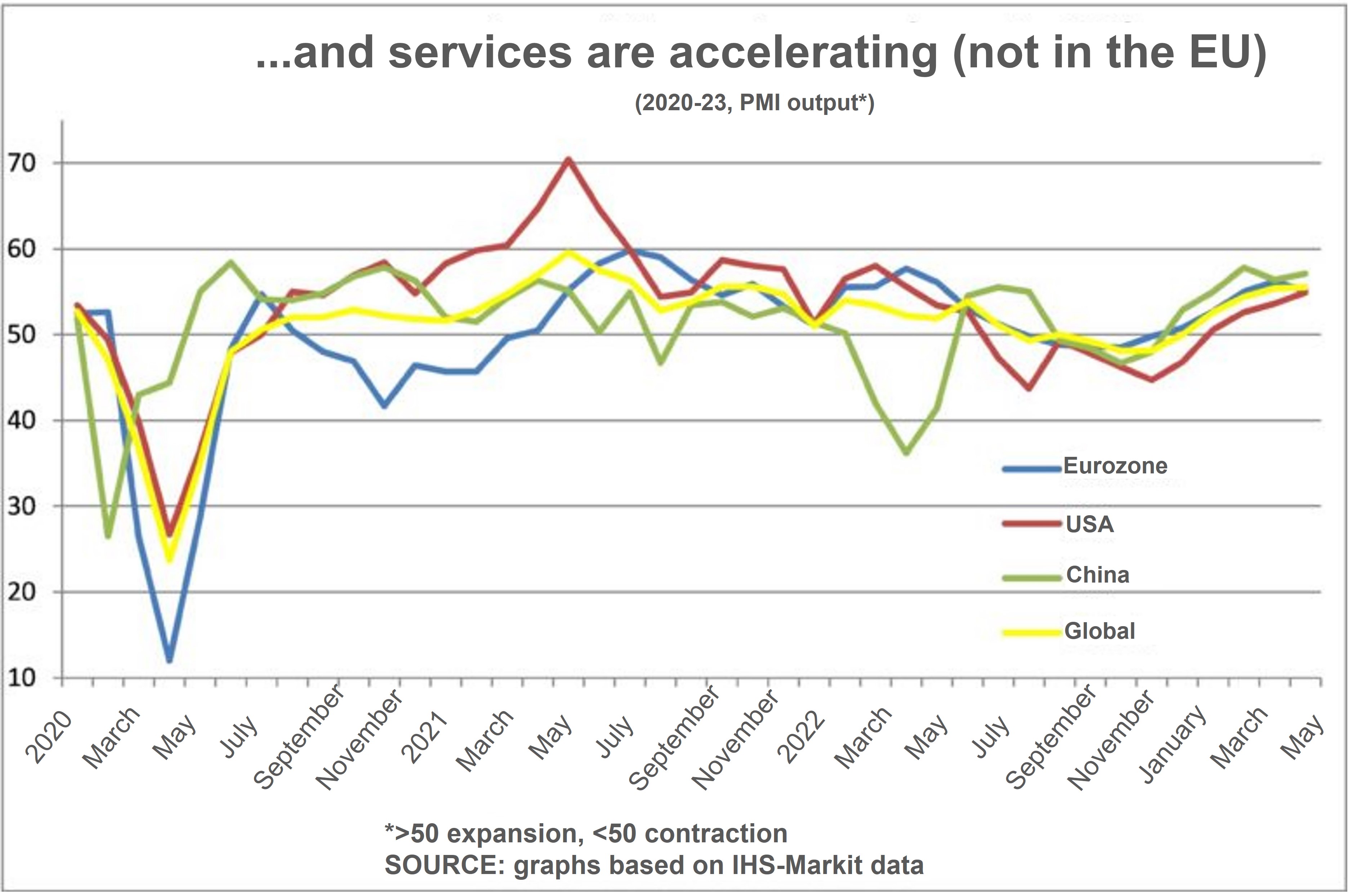

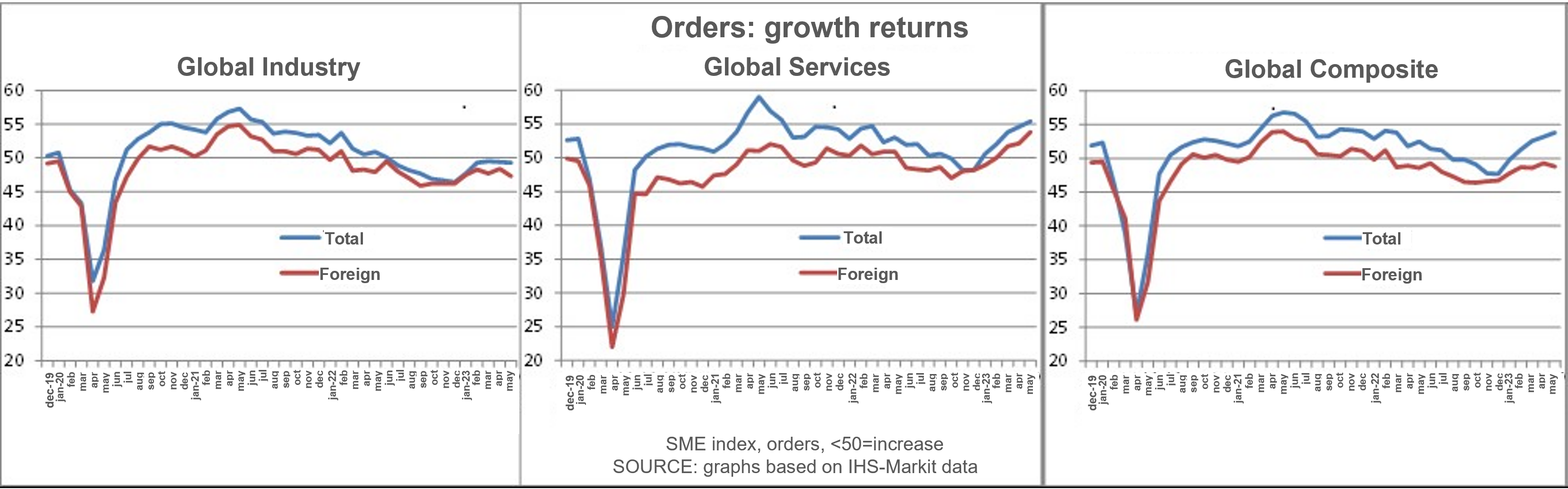

Widening our gaze to the entire globe, we observe that orders are growing overall, but as they are increasing in services, they are tending to decrease in industry.

This industry-service sector gap can also be seen in the current trends in output. With an unpleasant extra for us: Europe appears to be in trouble, either because its manufacturing is contracting or because its services are decelerating, whereas elsewhere they are accelerating.