The culture economy

by Luca Paolazzi

Can culture feed us? In other words, does culture contribute towards the formation and growth of GDP, and therefore of our material, as well as our spiritual, well-being?

The issue has always generated a great deal of controversy between those who believe that you can't survive on the basis of culture and those who believe that culture is a huge attraction for the growing number of travellers in the globalised world. The former include those who believe that humanistic studies offer few job opportunities for young people. While those who work in tourism undoubtedly agree with the latter. However, even in this case the most important aspects and the deepest links between culture and the economy are not fully grasped.

In fact, the vision of culture as an element of attraction recalls the attitude one has when faced with an oil field and originates from two distorted ideas of culture. The first is that it is something that comes to us from the past and is therefore essentially dead. A bit like oil which is born from the chemical transformation of plant remains and other biological beings deposited on the seabed. Deceased beings, as we said. The second is that exploitation of this "cultural deposit" is a source of unearned income, with an extractive approach to the economic activity that revolves around it. Of course, tour operators are businesses that live in a highly competitive context and must be resourceful and work hard to gain travellers from all over the world. However, being able to count on the charm of the cities of art or the incomparable beauty of Italian landscapes offers a competitive advantage that they found at their feet through sheer luck.

These are two typically Italian visions of culture which are closely linked: first of all, culture is an elitist matter, reserved for the few who understand it and who form a community of their own, a closed community; what's more, cultural heritage must be managed in an extremely conservative way, and woe betide you if you move even a single stone, let alone for reasons of economic initiative. Despite these concepts and visions, Italians have long known and still know how to turn culture into economic value, in ways that are very different from mere tourism, even if in the vast majority of cases they do so unconsciously, more or less unaware that they are doing it. These are filtered by two other visions that are very different from the previous ones; visions based on the living and vital role of culture, even that petrified in monuments, palaces, remains of cities and ancient civilisations. The first one gives culture a key role in creating identity: being born and growing up in places of great beauty marks us, gives us an imprint, distinguishes us from people who live in places that are much less rich in terms of landscape and history. The second vision is linked to the first: culture is a source of creativity and innovation, because it inspires the mind and nourishes the spirit of beauty.

For some, this creative process takes place through a codified path and an almost scientific method. Even if in this case the influences of culture are by no means exclusively rational. For the vast majority of the Italian population, however, assimilation of the beauty that surrounds us is osmotic, and therefore involuntary. In other words, the process is similar to the one that generates the production of vitamin D in the skin thanks to the sun's rays.

One way or another, it happens that in Italy the creative industries (extended by us to fashion) know how to multiply the added value of cultural activities (visits to museums, festivals, exhibitions, theatres, concerts) to an extent unknown in other advanced European countries: six times, versus two in France, Germany, the Netherlands and the United Kingdom i.e. every euro generated by cultural productions becomes six euros in creative+fashion productions. It is what we have called "the beautiful and well-made" Italian products which typify the production of the many industrial districts that dot the peninsula. On the other hand, Antonio Stoppani consecrated it as Il Bel Paese, reiterating the name that the verses of Dante ("del bel paese là dove ‘l sì sona") and Petrarch ("il bel paese ch'Appennin parte, e 'l mar circonda e l'Alpe") unequivocally identify.

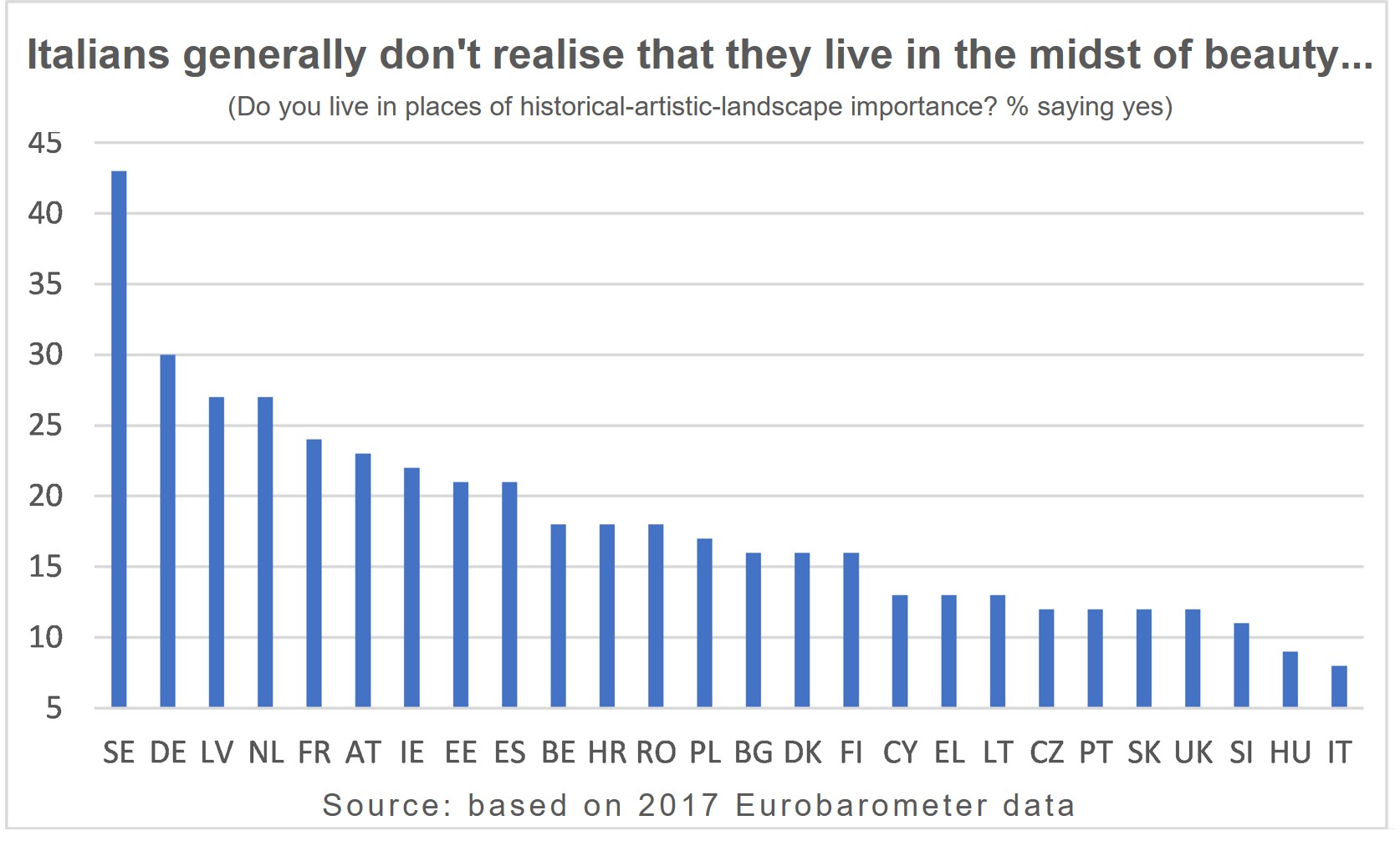

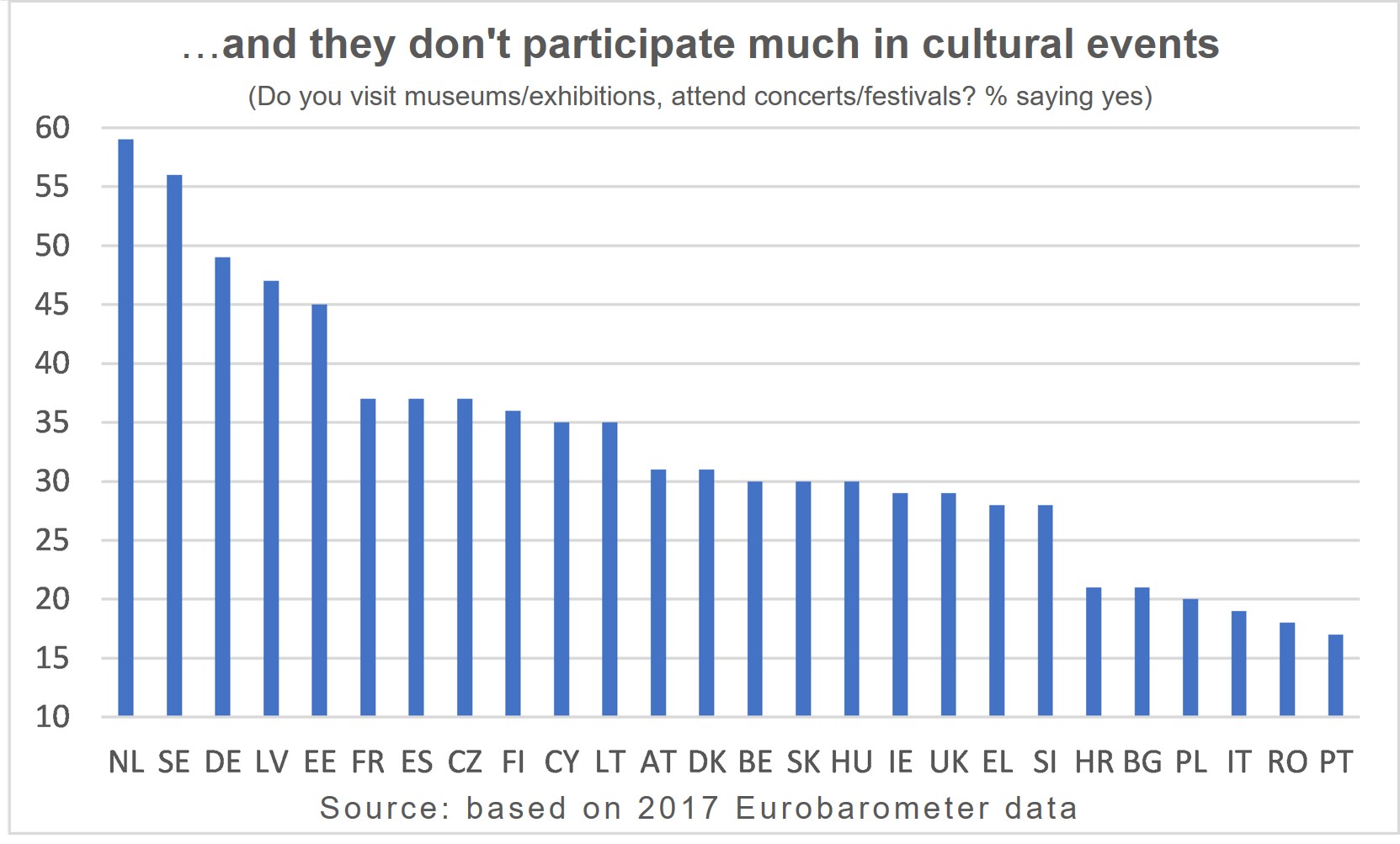

So everything's fine? No, unfortunately. Because this very beautiful rose has two very large thorns. Plus a third one that is very poisonous. The two thorns are that no other European country does and spends so little on culture as Italy. Which is a real contradiction born precisely of that concept according to which you can't survive on culture. What company wouldn't focus even more on a business that can expand up to six times? The second thorn, again by virtue of that unfortunate conception of culture as something elitist, is that Italians participate very little in cultural activities and largely feel excluded from them. Once again: if unconsciously feeding on beauty leads to an ability to generate beautiful and well-made products that conquer world markets, what would happen if this nourishment were conscious and more consistent by getting people more involved?

And the poisonous thorn? They are the young people who go abroad to seek their fortune and who, when interviewed by the Fondazione Nord Est, say that the only positive feature of living in Italy is the high level of art and culture on offer. But it's not enough to keep them here. Also in this case, if Italy played the culture card that history has given it more effectively, young people would be more involved in every working environment and there would be greater meritocracy, responsibility, decision-making autonomy...

What a lot of things culture brings with it! And there are still those who are convinced that you cannot feed on culture...